The financial markets have evolved significantly over the past few decades, particularly with the advent of electronic trading. Large institutional players—like hedge funds, mutual funds, and investment banks—often need to trade massive quantities of shares without tipping off competitors or influencing the market price. To facilitate this, a specialized category of trading venues called dark pools has emerged.

In this in-depth article, we will explore the concept of dark pools, their origins, how they operate, the role they play for institutional investors, and the advantages and disadvantages they bring to the financial markets. By the end, you will have a comprehensive understanding of how dark pools work, the reasons behind their popularity, and the controversies that surround them. This guide runs ensuring a deep dive that covers everything from historical contexts to modern-day regulatory challenges.

Table of Contents

Introduction to Dark Pools

In traditional stock markets like the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) or NASDAQ, trades are executed on a centralized and public order book. Every participant can see the bids and offers as well as the sizes at which buyers and sellers are willing to trade. However, this transparency can be both a blessing and a curse for large institutional players.

When an institution needs to buy or sell a sizable block of shares—say, hundreds of thousands or even millions—showing that order on a public exchange can lead to front-running or cause market impact, pushing the price higher (or lower) before the trade can be completed. Dark pools were introduced as a solution, allowing these trades to be hidden from public view, at least until the execution is finalized.

Why “Dark”?

The term “dark” in dark pools refers to the lack of pre-trade transparency. Information about orders (such as size, price, or who is trading) is concealed until after the trade has been executed—or sometimes not publicly disclosed at all. This contrasts with “lit” markets, where orders are visible on the limit order book in real-time.

Key takeaway: Dark pools offer anonymity and reduced transparency, which can help large traders avoid telegraphing their intentions to the market.

Historical Context & Evolution

Early Innovations: The Rise of Electronic Trading

Decades ago, trading was conducted through floor specialists and open outcry systems. As technology advanced, Electronic Communication Networks (ECNs) emerged, automating order matching and reducing the need for a physical exchange floor. ECNs provided:

- Greater speed of execution

- Lower transaction costs

- Accessibility to retail and institutional traders alike

However, ECNs (also known as “lit” electronic platforms) still display quotes and orders to all participants, making them susceptible to the same issues as traditional exchanges, namely market impact for large orders.

The Birth of Dark Pools

Dark pools date back to the 1980s, when major brokerage firms set up internal crossing networks to match large buy and sell orders internally. Over the years, these proprietary systems evolved into specialized platforms that institutional investors use to minimize the impact of large trades. According to some estimates, dark pools now account for roughly 15% of all trading volume in the US market, though this number can fluctuate.

Growth Catalysts

Several key factors have fueled the growth of dark pools:

- Electronification of Markets: As trading became more digital, it became easier to create alternative venues.

- Regulatory Changes: In the United States, Regulation ATS (Alternative Trading System) provided a framework for electronic trading platforms outside of traditional exchanges.

- Institutional Needs: Large mutual funds and pension funds frequently trade big blocks of shares, creating consistent demand for a venue that reduces visibility and market impact.

- High-Frequency Trading (HFT): The rise of HFT on lit markets created more urgency for institutional players to find ways to hide their large orders from predatory algorithms.

Understanding Dark Pools: Definition & Core Principles

What Exactly Are Dark Pools?

Dark pools are private electronic trading venues (or Alternative Trading Systems, ATS) designed specifically to facilitate block trades without revealing too much information to the broader market. The core objectives are:

- Anonymity: Conceal large orders so as not to tip off competitors.

- Reduced Market Impact: Execute big trades without causing significant price fluctuations.

- Internal Matching: Dark pools often match buy and sell orders internally, rather than routing them out to external exchanges.

Off-Exchange & Hidden

A dark pool is considered off-exchange because it operates outside the public quote and trade reporting mechanisms of major exchanges (though the trades are reported after execution for regulatory compliance). Unlike lit markets where the National Best Bid and Offer (NBBO) is publicly displayed, dark pool participants only discover the final execution price after the trade is filled.

Role of Institutional Investors

Dark pools cater primarily to institutional traders. Hedge funds, pension funds, and large asset managers often require an efficient way to accumulate or liquidate significant positions without sending signals to the market. This is particularly critical for long-term investors who don’t want short-term speculators or high-frequency traders front-running their trades.

Key Challenges Addressed by Dark Pools

Front-Running in Lit Markets

One of the most pressing concerns in the lit market is front-running, where other market participants exploit visible orders to trade ahead of a large position. This is especially problematic with:

- High-Frequency Trading (HFT): These traders use ultra-fast computers and proprietary algorithms to detect large incoming orders and react almost instantly, potentially pushing prices up (if they detect a large buyer) or down (if they detect a large seller).

- Information Leakage: Even partial revelation of a large order size can cause professional trading desks to move the market in anticipation.

Market Impact & Price Movements

Placing a large block trade on a public exchange often moves the market in an unfavorable direction for the trader. For instance, if an institution tries to buy 500,000 shares of a company on a lit exchange, other participants will see the growing demand and might:

- Increase their offers (driving the price up).

- Purchase shares ahead of the order to sell them back at a higher price later.

By keeping these trades hidden in a dark pool, institutions reduce the visible supply and demand signals they emit to the market.

How Dark Pools Work: Mechanisms & Processes

Basic Workflow

- Order Submission: An institutional trader sends a buy or sell order to a dark pool. This order typically includes parameters such as the desired size, time in force, and price limits (e.g., not exceeding $14 for a buy).

- Non-Display: Unlike lit markets, this order does not appear on any public order book. It resides in the dark pool’s internal order book, invisible to outside participants.

- Price Validation: Dark pools generally ensure trades are executed at or within the National Best Bid and Offer (NBBO).

- Matching: If there is a corresponding opposing order in the pool (or connected dark pools), a match occurs. If not, the order sits in the dark pool until it finds a suitable match or the time in force expires.

The Role of the NBBO

An important regulatory requirement for many dark pools is that they must price trades at or within the NBBO set by the lit exchanges. This ensures that dark pool trades don’t disadvantage one side of the transaction by crossing a public quote that is already available on a lit market.

Example: If the best bid is $10 and the best offer is $11 in the lit market, any matching in a dark pool will often need to occur within that range. In some cases, dark pools use a midpoint pricing mechanism, meaning the execution price is the midpoint between the current bid and ask (i.e., $10.50 in this example).

Executions & Reporting

Once a trade is matched in a dark pool:

- Execution Confirmation: Both the buyer and seller receive confirmations of the trade.

- Trade Reporting: Depending on local regulations, the trade may need to be reported publicly within a certain time limit. This disclosure is usually after the fact—post-trade—so competitors only see the activity with a delay.

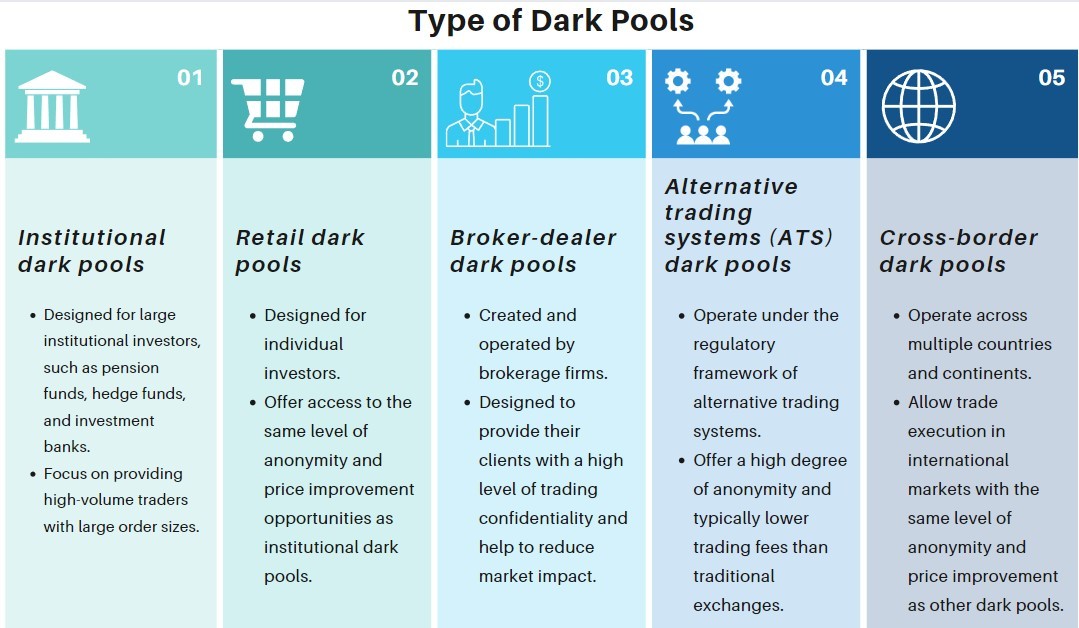

Types of Dark Pools

Not all dark pools are created equal. While they share common characteristics (anonymity and lack of pre-trade transparency), there are different operating models:

- Broker-Dealer-Owned Dark Pools

- Operated by large banks or brokerages (e.g., Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley).

- Primarily serve the clients of that broker-dealer, matching orders internally.

- Exchange-Owned Dark Pools

- Some major exchanges operate their own dark pool platforms, providing an alternative venue under the same corporate umbrella.

- Independent Dark Pools

- Independent firms that specialize in crossing large orders, often providing access to multiple liquidity sources.

- Consortium Dark Pools

- Owned by a group of broker-dealers or institutional investors.

Each dark pool has its own rules for matching orders—some prioritize time in queue, others emphasize size of order, or even price improvement. This variety in matching algorithms is a defining feature and makes it harder for external traders to game or predict how trades will be executed.

Advantages of Dark Pools

1. Reduced Market Impact

Market impact occurs when large orders shift the prevailing market price. By hiding these orders until execution, dark pools help institutional traders avoid the price moving against them. This is particularly valuable when building or unwinding a large position.

2. Potential for Better Pricing

Dark pools often use the midpoint of the NBBO to execute trades, meaning the buyer might pay less than the prevailing offer, and the seller might receive more than the prevailing bid. This price improvement can be significant for large transactions.

3. Anonymity and Confidentiality

Institutions rely on stealth to maintain their competitive edge, especially with proprietary trading strategies. The anonymity offered by dark pools prevents other market participants from capitalizing on visible order flow information.

4. Lower Transaction Fees

In some cases, dark pools offer lower fees than trading directly on public exchanges. For large institutions executing high-volume trades, even a small reduction in fees can translate into substantial savings.

5. Mitigation of High-Frequency Trading (HFT)

Since dark pool orders are not visible, high-frequency traders have fewer opportunities to detect large blocks and jump in front of them. While not entirely eliminating HFT concerns (as we’ll see later), dark pools do help minimize exposure to algorithmic front-running.

Disadvantages & Controversies

1. Lack of Transparency

By definition, dark pools provide minimal pre-trade transparency. Critics argue that this reduced visibility can fragment markets, making it harder to get a clear picture of supply and demand. Moreover, regulators and smaller market participants worry that the hidden nature of dark pools can lead to unfair advantages for large players.

2. Regulatory Scrutiny

Because they operate outside the public eye, dark pools have been subject to intense regulatory focus. Regulators fear that dark pools, if left unchecked, could undermine market integrity, facilitate insider trading, or enable other manipulative practices.

Case in Point: In the United States, the SEC has pursued cases against broker-dealers for misleading clients about how their dark pools operate. In Europe, MiFID II introduced new rules limiting dark pool trading through caps on how much volume could be executed in these venues under certain conditions.

3. Potential for Unfair Practices

While dark pools are designed to mitigate front-running, there have been instances where high-frequency trading firms gained preferential access to certain dark pools. This can lead to “dark pool arbitrage,” where HFTs exploit small price differences or detect patterns in order flow. When these scenarios arise, it undermines the very purpose of dark pools and calls their fairness into question.

4. Complexity & Fragmentation

With dozens of dark pools in operation, each with its own matching rules and fee structures, the market becomes highly fragmented. Participants need sophisticated smart order routing (SOR) technology to navigate multiple venues effectively, which can be costly and complex to maintain.

Front-Running & Pinging: How Traders Try to Exploit Dark Pools

1. The Concept of Pinging

One of the more nuanced tactics in dark pool trading is pinging, where traders send small orders (often in very small share quantities) to probe whether there is significant buy or sell interest at a given price level within a particular dark pool.

How It Works:

- The trader (or HFT firm) submits a tiny sell order—say, 100 shares—in the dark pool.

- If the order gets filled instantly, that’s a signal: there’s likely a large buyer lurking at or above that price.

- The trader then rushes to buy shares on the open market (lit market) before the large buyer can push prices higher.

- By accumulating shares cheaply, they can resell them—often back into the dark pool—at a higher price, effectively front-running that large institutional buyer.

2. Impact of Pinging on Large Investors

Despite dark pools’ secrecy, pinging can still reveal enough information to savvy, technology-driven traders. This undermines one of the primary benefits of dark pools—anonymity. However, as dark pools become more sophisticated, they have introduced countermeasures like:

- Minimum Order Sizes to block pinging with tiny orders.

- Latency or Speed Bumps to slow down opportunistic HFT strategies.

- Cancellation Fees or Restrictions to discourage rapid-fire orders that do not result in trades.

3. Real-World Example of Pinging

Imagine a situation:

- A large institution wants to buy 20,000 shares at a maximum of $14 per share.

- The best lit market quote is $10 (bid) and $11 (ask).

- HFT firm pings the dark pool with a 100-share sell order at $10.50.

- If it immediately gets filled, the HFT firm deduces there’s a big buyer lurking.

- The HFT firm then buys as many shares as possible at $11 on the lit market, raising the price.

- They incrementally sell back into the dark pool at slightly higher prices each time, effectively front-running the large buyer.

This sequence illustrates how, despite the goal of concealment, dark pools can still be partially exposed by persistent “testing” or “pinging” from determined traders.

Regulatory Framework & Oversight

United States: SEC & FINRA

In the U.S., dark pools are classified as Alternative Trading Systems (ATS) and are regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and monitored by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA). Key regulations include:

- Regulation ATS: Requires dark pools to register and comply with certain disclosure requirements.

- Reporting Requirements: Dark pool trades must be reported to a Trade Reporting Facility (TRF) for post-trade transparency within specified timeframes.

- Fair Access: Larger ATSs are required to provide fair access and not discriminate among participants.

Europe: MiFID II

In Europe, dark pools are regulated under MiFID II (Markets in Financial Instruments Directive II), which imposes:

- Volume Caps: Limits on how much trading can take place in dark pools for a specific stock relative to overall volume in the lit market.

- Waivers: Certain orders (like large-in-scale trades) receive waivers from pre-trade transparency, enabling them to execute in dark pools without public display.

These regulations aim to balance the benefits of dark pools with the broader market’s need for transparency and fairness.

Other Jurisdictions

Across Asia and other markets, regulatory attitudes towards dark pools vary widely. Some markets actively encourage them to attract institutional liquidity, while others impose stricter rules to ensure that a majority of trades remain in public view.

Comparing Dark Pools to Other Execution Methods

Lit Markets & Exchanges

- Transparency: Orders are visible, which can lead to front-running of large trades.

- Liquidity: Generally higher volumes, especially for popular stocks.

- Price Discovery: Price formation is more robust because quotes are public and the market can react immediately.

ECNs

- Electronic Communication Networks (ECNs) are “lit” venues but fully electronic.

- Often used for after-hours or pre-market trading, as well as high-speed trading by HFTs.

- Advantages: Speed, transparency, and broad accessibility.

- Disadvantages: Similar risk of market impact if large orders are shown.

Block Trades & Upstairs Markets

Before dark pools, block trades were executed in so-called upstairs markets, where broker-dealers negotiated off-exchange trades among large clients. Dark pools formalize this process electronically, offering a more systematic and rule-based environment than traditional “upstairs” dealing.

Iceberg Orders

Some lit exchanges allow “iceberg orders,” where only a portion of the total size is displayed, and the rest is hidden. This is another method to conceal large positions but still not as private as an entire off-exchange venue.

Real-World Examples & Case Studies

Barclays LX Dark Pool

One high-profile regulatory case involved the Barclays LX dark pool. Barclays was accused by regulators of misrepresenting the level of HFT activity within its dark pool, among other charges. The case highlighted:

- Transparency vs. Secrecy: Investors and regulators want to know who is trading against them, but dark pools by nature obscure that.

- Mislabeling Risk: Barclays allegedly claimed that certain HFT strategies were banned or minimized, when in fact they were prevalent.

Morgan Stanley’s MS Pool

Morgan Stanley’s dark pool offers a large crossing network for the firm’s clients. While it aims to provide price improvement and better execution for institutional orders, it has faced its share of scrutiny over how it routes and matches orders internally.

These examples underscore the tension between providing a secure environment for large trades and ensuring the fairness and integrity of the overall market.

Who Uses Dark Pools & Why?

Institutional Investors

- Mutual Funds and Pension Funds: Large, long-term investments often require big trades.

- Hedge Funds: Might use dark pools for stealth accumulation or liquidation.

- Investment Banks & Broker-Dealers: Internalize client order flow and reduce external market impact.

High-Frequency Traders

Some HFT firms participate in dark pools, especially those that allow for smaller order sizes, aiming to arbitrage slight price differences between lit and dark venues. This practice is controversial as it can negate the very benefits the dark pool promises.

Retail Traders

Retail involvement in dark pools is typically indirect. When you place an order through a brokerage, your broker might decide whether to route your order to an exchange, a dark pool, or another internal matching engine. Retail traders usually do not interact with dark pools directly—at least, not with the same discretionary control as institutional clients.

Practical Insights for Traders

Smart Order Routing (SOR)

In today’s fragmented market, brokers use smart order routers to find the best possible execution venue, whether that be a lit exchange, ECN, or dark pool. SOR algorithms:

- Check the NBBO in real-time

- Evaluate multiple dark pools for liquidity

- Consider transaction fees and potential price improvement

Time & Sales Analysis

For active traders, analyzing the time and sales feed can reveal patterns of dark pool activity. You may see large block trades reported off-exchange, often with a delay. Frequent dark pool prints can signal that institutions are active in a particular stock, possibly hinting at upcoming price movements.

Limit vs. Market Orders

When trading in or around dark pools, limit orders offer control over the maximum (or minimum) price you will accept. Large institutional traders often set a limit (e.g., not buying above $14) to control their average price. Market orders in a dark pool scenario can be risky if liquidity isn’t there at the moment of execution.

Watching for Pinging

While individual retail traders can’t typically “ping” dark pools effectively, it’s useful to know that it happens. If you see sudden, small trades at multiple price points in a short span, it might be indicative of an entity testing the waters for hidden liquidity.

Future Outlook of Dark Pools

Increasing Regulation & Transparency

Regulators worldwide are scrutinizing dark pools to prevent abuse. Expect further reporting requirements, potential volume caps, and transparency measures that aim to maintain market integrity while still allowing large trades to remain discreet.

Technological Advances

As algorithmic trading becomes more advanced, dark pools will continue adapting:

- Speed Bumps to deter HFT front-running.

- Enhanced Matching Algorithms that prioritize genuine block trades over rapid-fire small orders.

- Big Data Analysis to detect manipulative behaviors.

Ongoing Debate: Fairness vs. Efficiency

The fundamental debate centers on whether dark pools, by limiting transparency, harm market price discovery or enhance efficiency for large institutional trades. Striking a balance between these competing priorities will define the trajectory of dark pools in the coming years.

Conclusion

Dark pools are a critical yet controversial part of the modern trading ecosystem. They provide large institutions the means to buy and sell substantial blocks of shares discreetly, minimizing market impact and reducing the risk of front-running. Their anonymity and lack of pre-trade transparency have been both lauded—for facilitating large trades efficiently—and criticized—for potentially fragmenting the market and allowing room for unfair practices.

From pinging tactics designed to expose hidden liquidity, to regulatory clampdowns aimed at ensuring fairness, dark pools occupy a dynamic niche where technology, regulation, and market participant interests converge. For institutional traders, dark pools can offer better pricing and lower transaction costs. For regulators and some smaller participants, the secrecy remains a point of unease, as it can obscure the true supply and demand in the overall market.

Despite these concerns, dark pools show no sign of disappearing. They have become integral to how modern equity markets function, enabling large trades that might otherwise cause massive price disruptions on public exchanges. For anyone active in the stock market—be it institutional or retail—understanding the mechanics, advantages, and risks of dark pools is essential.

Key Takeaways:

- Reduced Visibility: Orders are hidden until execution, helping large traders avoid front-running.

- Market Impact Mitigation: Dark pools limit price swings caused by huge block trades.

- Regulatory Pressure: Growing scrutiny aims to prevent market fragmentation and insider abuses.

- Pinging & HFT: Sophisticated players still attempt to expose large hidden orders through small test trades.

- Future Trajectory: Expect more regulation, evolving technology, and an ongoing debate over the balance between efficiency and transparency.

As financial markets continue to evolve, the role of dark pools will remain under close observation—a dance between the benefits of hidden liquidity for large trades and the broader market’s need for transparency and equitable price discovery.