In the world of finance, one question seems to pop up endlessly: “Is the stock market truly predictable?” Investors, economists, and academics have been wrestling with this for decades. On one side, there are traders and analysts who believe that with enough skill, data, and insight, they can beat the market. On the other side, there are those who argue it’s all but impossible to consistently outperform a market teeming with informed participants.

At the heart of this debate lies the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH). Formulated in various stages by a number of economists—most famously by Eugene Fama in the 1960s—EMH proposes that financial markets are extremely efficient in reflecting all available information. According to this theory, the market’s price is as close to “correct” as it can be, making it nearly impossible to consistently find mispriced assets and profit from them in a systematic way over the long term.

In this article, we will delve deeply into the nuances of EMH. We’ll explore its forms (weak, semi-strong, and strong), its core assumptions, and the various criticisms and counterarguments that have emerged over the years. We will also examine practical implications for investors—where the theory stands in terms of guiding investment strategies—alongside alternative perspectives that might challenge or complement the hypothesis. By the end, you should have a well-rounded view of whether the stock market is truly predictable and how EMH fits into your investing philosophy.

Table of Contents

What Is the Efficient Market Hypothesis?

The Efficient Market Hypothesis posits that financial markets incorporate and reflect all relevant information at any given time. The idea suggests that stock prices at any moment already account for past events, current public data, and even investor expectations about the future. As new information emerges—be it a company’s earnings report, a change in macroeconomic indicators, or geopolitical news—market prices adjust almost instantaneously to the “fair value.”

Key Takeaways

- Information is instantly priced in: According to EMH, no investor can consistently benefit from a system of picking undervalued stocks or identifying overvalued ones once all relevant information is public.

- Randomness in price movements: Price movements become more or less random because any predictable component of price changes would be arbitraged away quickly by market participants.

- Investor rationality assumed (to an extent): EMH assumes that the collective actions of market participants are rational or that irrational trades cancel out as investors act on mispricings.

Notably, if all these conditions are true, then any attempt to “beat the market” consistently (after factoring in transaction costs, taxes, and other fees) is futile. This viewpoint has shaped a myriad of investment strategies and academic research.

Historical Context and Development of EMH

The underpinnings of EMH can be traced back to the early 20th century, although the formal framework emerged more clearly in the 1960s.

- Louis Bachelier (1900): Often cited as one of the earliest contributors to the idea, Bachelier’s work on the theory of speculation included mathematical formulations suggesting that asset prices follow a “fair game” model. This is sometimes regarded as a precursor to the random walk concept in finance.

- Paul Samuelson (1960s): Nobel laureate Paul Samuelson provided a key theoretical backdrop for market efficiency. Samuelson’s insight was that a market in equilibrium under competitive conditions and rational expectations would adjust prices so that no arbitrage opportunities remained.

- Eugene Fama (1970): In his seminal paper, “Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work” Fama synthesized previous ideas and provided a structured, testable framework. He categorized market efficiency into three forms—weak, semi-strong, and strong—each reflecting different sets of available information.

- Further Academic Research (1970s-1980s): Researchers like Michael Jensen, Richard Roll, and Stephen Ross continued to examine empirical data to test the validity of EMH. This era saw an explosion of statistical tests to see if stock prices reflected historical, public, and private information efficiently.

- Challenges & Alternatives (1980s-1990s): While EMH dominated much of the academic landscape, new streams of thought began to emerge. Behavioral finance scholars like Robert Shiller and Richard Thaler highlighted systematic biases and irrationalities in investor behavior, leading to a vigorous debate about the real extent of market efficiency.

Today, EMH remains foundational in modern finance. It influences everything from how mutual funds are structured (passively vs. actively managed) to how regulatory bodies approach market transparency.

The Three Forms of EMH

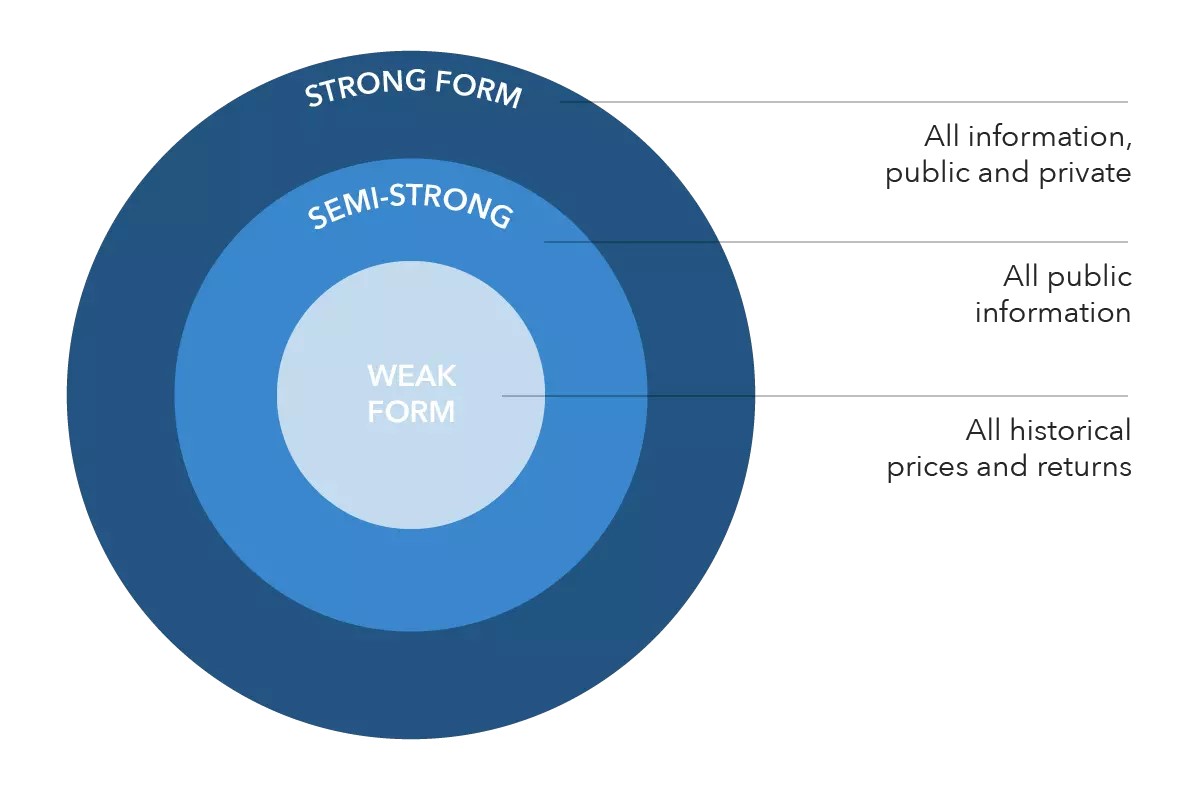

In his influential work, Eugene Fama proposed three versions of market efficiency based on different levels of information access. These forms—weak, semi-strong, and strong—helped give structure to how we test or interpret efficiency in real-world markets.

Weak Form EMH

- Definition: The weak form states that current stock prices fully reflect all historical price and volume data. In other words, any patterns or trends that can be gleaned from past trading data (such as technical indicators) are already priced into the market.

- Implication: Under weak form efficiency, technical analysis should not provide any systematic advantage. If the market already incorporates all past price movements, then looking at chart patterns or moving averages, for instance, does not yield a dependable edge.

- Example: Suppose a technical analyst identifies a trend that historically suggests a stock is about to go up. According to the weak form EMH, this historical pattern would already be reflected in the current price because the market collectively recognizes those signals.

Semi-Strong Form EMH

- Definition: The semi-strong form asserts that prices reflect not only historical data but also all publicly available information. This includes financial statements, news reports, analyst opinions, and economic indicators. Essentially, any piece of info that is available to the general public is instantly priced in.

- Implication: Even fundamental analysis cannot consistently produce risk-adjusted returns that beat the market because by the time you finish analyzing public data, the market already knows it, and the price has adjusted accordingly.

- Example: If a company announces an earnings surprise, the semi-strong form suggests the stock price will move almost immediately to reflect this new information. Buying the stock right after the announcement wouldn’t necessarily yield excess returns, because the “good news” is already captured in the new price.

Strong Form EMH

- Definition: The strong form goes a step further, claiming that all information, public and private, is already accounted for in stock prices. This means even insider information or undisclosed data is theoretically priced into the market.

- Implication: No one can achieve consistently higher returns on a risk-adjusted basis—not even corporate insiders. This form is the most restrictive and contentious because it implies that illegal insider trading would not yield consistent excess profits (a stance that real-world prosecutions of insider trading obviously dispute).

- Example: An executive within a corporation, having knowledge of a pending merger, would not be able to profit from that knowledge if the market were perfectly strong-form efficient. However, numerous insider trading cases have shown that people do profit from non-public information, suggesting strong-form efficiency is more theoretical than practical.

Core Principles and Assumptions of EMH

For EMH to hold, certain core principles and assumptions typically underpin the hypothesis. While real-world conditions often differ, these assumptions guide the logic behind why market prices might be “efficient.”

1. Perfectly Rational Investors

One major assumption is that investors are rational in aggregate. When new information surfaces, these rational investors quickly assess its impact on the company’s valuation, and trades occur that push the price to a new equilibrium.

- Reality Check: Behavioral economists argue that investors are not always rational. Emotions such as greed and fear, along with cognitive biases, can lead to irrational market behavior—evidenced by bubbles (e.g., the Dot-Com Bubble) and crashes (e.g., the 2008 Financial Crisis).

2. No Transaction Costs

Another assumption is that there are no or minimal barriers to trading. This assumption ensures that any price discrepancies are quickly eliminated because participants can arbitrage away these discrepancies at no cost.

- Reality Check: In real markets, transaction fees, bid-ask spreads, taxes, and liquidity constraints are very real. For example, if you notice a mispriced stock that’s off by a few cents but your brokerage fee is large, you cannot profit from that discrepancy.

3. Perfect Information Flow

EMH assumes that relevant information flows freely and instantaneously to all market participants. No single investor has a time advantage or an exclusive data feed that others do not.

- Reality Check: In practice, high-frequency traders can gain minute advantages by having servers physically closer to the exchange. Insider information leaks also happen, giving some traders an unfair edge. The existence of these phenomena raises questions about absolute market efficiency.

EMH vs Random Walk Theory

It’s common to hear Random Walk Theory mentioned alongside EMH. The two concepts are closely related but not identical:

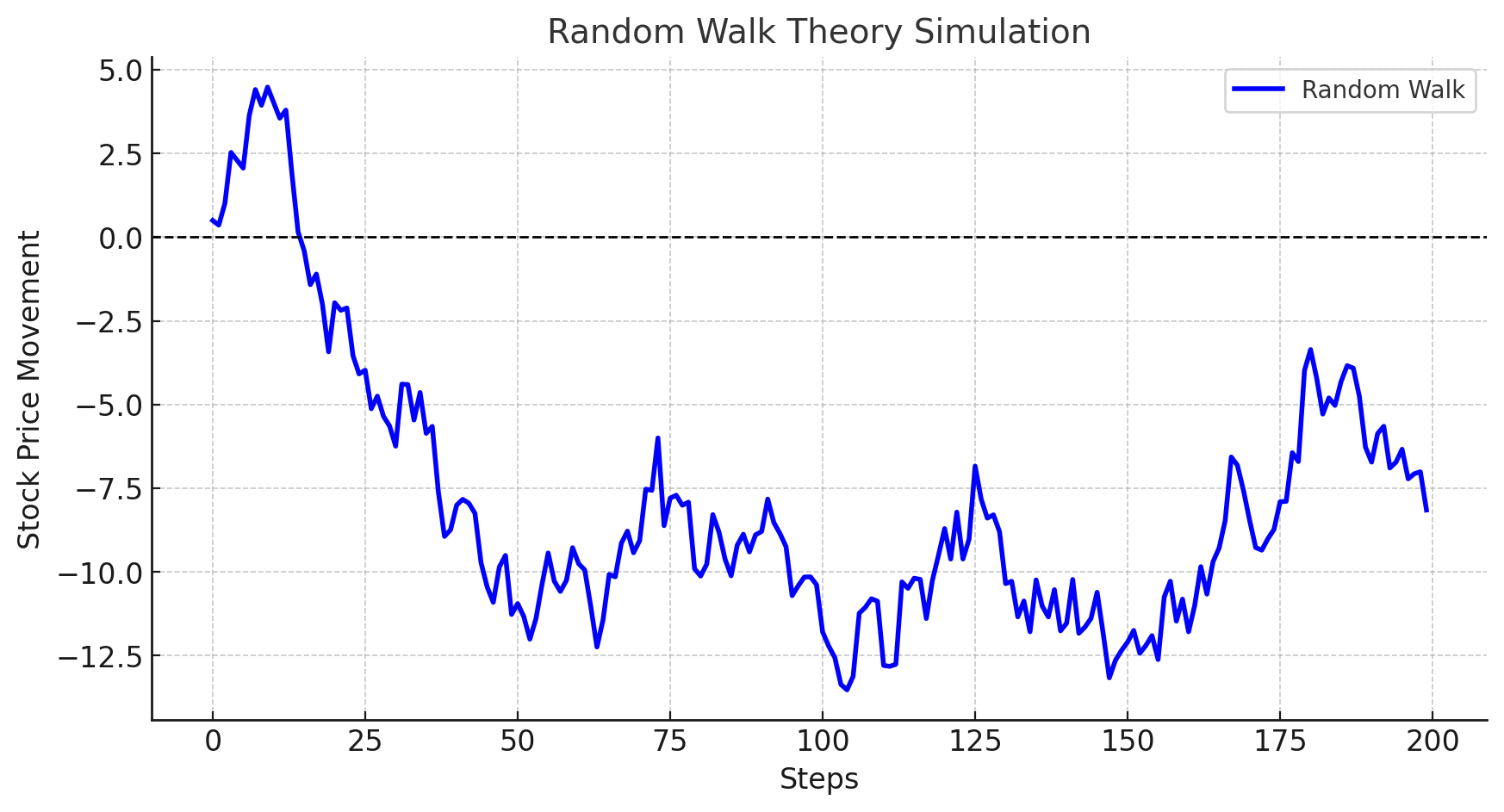

- Random Walk Theory: This idea posits that stock price changes are random and unpredictable. The future price is independent of past movements, much like coin flips do not depend on previous outcomes.

- EMH: EMH states that prices reflect all available information, leading to the conclusion that any predictable patterns are quickly eliminated by market forces.

Similarity: Both theories suggest it’s exceptionally challenging to predict short-term or long-term price movements. If the market is efficient, any predictable pattern would be exploited by investors until it disappears—thus resembling randomness.

Difference: Random Walk Theory is primarily about the statistical nature of price changes (no memory of past prices), whereas EMH is an information-based framework explaining how prices reach their current levels through rational investor action and information processing. However, the conclusion of both theories often aligns: you can’t systematically outperform the market just by analyzing historical data or common public information.

Criticisms and Limitations of EMH

Despite its central position in modern finance, EMH has been heavily scrutinized. Several real-world observations challenge the notion that markets are truly efficient at all times.

Market Anomalies

Market anomalies are patterns or events that contradict the EMH’s prediction of efficient pricing. Here are some notable ones:

- January Effect: Historically, small-cap stocks have often produced abnormally high returns in January. While explanations vary—from tax-related selling in December to institutional rebalancing—this recurring seasonal pattern raises questions about whether markets instantly price in all relevant information.

- Weekend Effect: Some studies show that stock returns on Mondays tend to be lower than on other days of the week, suggesting a possible inefficiency or behavioral component affecting prices after weekends.

- Momentum Anomaly: Research shows that stocks that have been rising over a certain short-term period (3-12 months) tend to continue rising in the subsequent short term. Conversely, stocks that have been underperforming tend to continue underperforming. This phenomenon suggests that past performance may offer some predictive power—counter to weak form EMH.

Behavioral Finance

Behavioral finance presents one of the most robust challenges to EMH. This field combines psychology and economics to understand how irrational behaviors and cognitive biases can influence market outcomes. Some key biases include:

- Herding Behavior: Investors often follow the crowd, buying into hot stocks or sectors simply because everyone else is doing it.

- Overconfidence: Many traders and fund managers overestimate their ability to interpret information or pick winning stocks, leading to excessive risk-taking.

- Loss Aversion: Investors tend to fear losses more than they desire equivalent gains. This can lead to irrational holding of losing stocks too long or selling winners too early.

These behaviors can create price distortions that persist longer than EMH would predict. Consider the case of speculative bubbles—such as the Dot-Com Bubble of the late 1990s—where stock prices soared despite questionable fundamentals. EMH struggles to explain why these irrational price run-ups were not instantly corrected.

Real-World Examples of EMH Being Challenged

- Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) Collapse (1998): A hedge fund run by Nobel laureates in Economics (Myron Scholes and Robert Merton) famously collapsed under extreme market conditions. Their sophisticated models assumed a level of rationality and normality in price movements that did not hold up during periods of crisis.

- Flash Crashes and High-Frequency Trading Glitches: Sudden, dramatic drops in stock prices (and equally rapid recoveries) in a matter of minutes or even seconds. These events reveal that algorithmic trading can cause temporary inefficiencies or extreme volatility that pure EMH doesn’t fully account for.

- Bubbles and Crashes (e.g., 2008 Financial Crisis): The housing market bubble and subsequent global financial crisis showed how markets might underprice risk or overprice assets for long stretches, contradicting the EMH premise that prices are always correct reflections of available information.

While EMH provides a neat theoretical framework, these anomalies and behavioral factors highlight that the real-world markets are more complicated than the idealized models would suggest.

Practical Implications for Investors

Whether you’re a day trader or a passive index investor, understanding EMH can influence how you approach the stock market. Here are several practical takeaways:

Active vs Passive Investing

- Active Investing: Managers attempt to pick stocks, time the market, or exploit pricing inefficiencies to outperform benchmarks. EMH suggests that this is difficult to do consistently, especially after fees.

- Passive Investing: Passive strategies (like buying index funds) are often recommended by proponents of EMH. They argue that paying hefty fees for active management typically does not pay off in the long run, and that broad market exposure yields competitive returns without unnecessary risk or expense.

The Role of Index Funds

Index funds reflect the market itself. If the EMH holds, an index fund (e.g., S&P 500 ETF) is already capturing the market’s best estimate of value at any given time. Historically, a significant portion of actively managed funds fail to beat their benchmark index net of fees, lending credibility to passive strategies.

- Example: Vanguard’s S&P 500 Index Fund (VFINX) has been used as a benchmark to compare against actively managed funds. Over many multi-year periods, the majority of actively managed funds underperform net of fees.

Technical Analysis vs Fundamental Analysis

- Technical Analysis: If the market is weak-form efficient, analyzing past price charts, volume spikes, and oscillators should not yield consistent excess returns.

- Fundamental Analysis: If the market is semi-strong form efficient, then poring over public financial statements and economic indicators to find undervalued companies may also be of limited benefit in beating the market, especially if everyone else is doing it.

Nevertheless, many investors still rely on a combination of technical and fundamental analysis. One justification is that even if the market is generally efficient, there might be pockets of inefficiency or times when market participants act irrationally, providing opportunities for skilled analysts.

Alternative Theories and Perspectives

EMH is not the only game in town. A range of alternative theories have emerged, aimed at explaining phenomena that classic EMH struggles to account for.

Adaptive Market Hypothesis

Proposed by economist Andrew Lo, the Adaptive Market Hypothesis (AMH) takes elements of EMH but infuses them with concepts from evolutionary biology and behavioral economics. The idea is that markets evolve over time, and participants adapt their strategies in response to changing conditions, competition, and innovation.

- Key Point: Markets can be efficient in some contexts but become inefficient when conditions change faster than participants can adapt. This helps explain why certain trading strategies work for a time but then stop working once they become too crowded or once market conditions shift.

Further Insights from Behavioral Economics

Behavioral economists continue to propose models where irrational investor behavior systematically affects prices. These models often incorporate:

- Prospect Theory (Kahneman & Tversky): People value gains and losses differently, feeling the pain of losses more acutely than the pleasure of gains.

- Heuristics and Biases: Investors use mental shortcuts (heuristics) like representativeness, anchoring, or availability, which can lead to price distortions.

The bottom line is that while EMH provides a baseline, real-world markets are influenced by human psychology, cognitive limitations, and even cultural or technological shifts.

Real-World Applications and Case Studies

Understanding how EMH applies in real-world scenarios can provide clarity on its practical limits and advantages.

- Index Fund Popularity:

- Over the past few decades, the exponential growth of index funds (from providers such as Vanguard, BlackRock, and State Street) can be seen as real-world endorsement of the semi-strong form of EMH.

- Retail investors find that owning a market-tracking index often outperforms the net returns of actively managed funds.

- Arbitrage Opportunities:

- In theory, if there’s a price discrepancy between two markets (e.g., a stock listed on two different exchanges), sophisticated traders will jump in to exploit that arbitrage until the prices converge.

- This rapid action often supports the idea of market efficiency—mispricings are corrected quickly.

- High-Frequency Trading (HFT):

- HFT firms use powerful computers and algorithms to capitalize on split-second price discrepancies.

- Their activities accelerate price discovery but can also introduce volatility. Events like the 2010 “Flash Crash” highlight that while HFT might bring prices closer to fair value under normal conditions, it can create chaos under extreme conditions.

- Case Study: Warren Buffett and Value Investing:

- Value investors like Warren Buffett at Berkshire Hathaway have outperformed the market for decades. Critics of EMH point to Buffett’s success as evidence that markets are not fully efficient.

- EMH proponents retort that Buffett is an outlier, and for every Buffett, there are countless active managers who fail to beat the market. They also mention that in large numbers, it’s statistically likely a few outliers will exist.

Is the Stock Market Truly Predictable?

This is the million-dollar question—can we predict the stock market? If EMH holds perfectly, the answer would be a resounding “no,” at least not in a way that outperforms passive index returns on a consistent risk-adjusted basis. Prices would move so swiftly to incorporate new information that any profit opportunity would be fleeting or non-existent.

However, real markets are populated by human beings, not just equations. Investors’ behavior, technology changes, macroeconomic shifts, and sudden global events (e.g., pandemics, wars, natural disasters) all contribute to volatility and instances of apparent mispricing. Could these moments be exploited to achieve market-beating returns?

- Short-Term vs. Long-Term Predictions: In the very short term (seconds to days), price movements can be extremely noisy, driven by order flows, market maker activity, and sentiment shifts. Over the long term (years to decades), markets have generally trended upward (at least in the U.S.), but predicting the path is complex.

- Market Cycles and Patterns: Some analysts argue that markets move in cycles—bull markets, bear markets, sector rotations—but precisely timing these shifts is notoriously difficult.

- Skill vs. Luck: Statistically, distinguishing skill from luck in trading is challenging. Even in a random distribution of outcomes, some traders will consistently “win” over a given time frame just by chance.

Ultimately, most academic research suggests that the stock market is not predictably beatable by the average investor, especially after fees and transaction costs. Yet, pockets of inefficiency and anomalies persist, and some skilled professionals do manage to outperform periodically. Whether that outperformance is due to true skill or a form of survivorship bias remains a topic of intense debate.

Final Thoughts

The Efficient Market Hypothesis has profoundly shaped modern finance, influencing everything from how mutual funds and ETFs are structured to how regulators approach transparency and disclosure. Its core proposition—that markets are adept at pricing in available information—offers a strong argument for why many active managers fail to outperform benchmarks.

Yet, as robust as EMH is, it does not fully capture the complexity of real-world markets. Behavioral biases, information asymmetries, transaction costs, and institutional factors all create situations where the market may not be perfectly efficient. Bubbles, crashes, and recurring anomalies highlight that investors do not always act rationally.

So, is the stock market truly predictable? Under strict interpretations of EMH, the answer leans towards “no.” However, markets do exhibit recurring patterns influenced by human psychology and macroeconomic cycles, giving partial support to the idea that skill and timing can matter—for some investors, some of the time.

For long-term retail investors, the practical advice often gleaned from EMH is:

- Adopt a diversified, low-cost, passive strategy (like index funds).

- Focus on your investment horizon and avoid frequent trading that racks up fees.

- Stay informed but avoid overreacting to short-term market news or price fluctuations.

For institutional and high-sophistication traders, understanding market microstructure and leveraging the latest technology or research can yield edges—but these edges often shrink quickly as more participants catch on.

In sum, while EMH might not fully explain every twist and turn in the markets, it remains a crucial framework for anyone seeking to understand why consistent, risk-adjusted market outperformance is so elusive. It challenges both professional money managers and do-it-yourself investors to question whether the quest for “alpha” is worth the cost—or if the wiser route is to simply align with the market’s inherent efficiency.