In modern financial markets, liquidity is often described as the lifeblood that keeps trading alive and efficient. It represents how quickly and easily assets can be bought or sold without causing drastic changes in their prices. But who is responsible for creating and maintaining this much-needed liquidity? This responsibility often falls on the shoulders of market makers—key players whose primary role is to ensure that markets remain active and accessible to all participants.

This comprehensive guide explores every aspect of market making, including its definition, the importance of liquidity, the mechanics of how market makers operate, and the risks and strategies involved. By the end, you’ll have an in-depth understanding of how market makers function, why they’re essential for market stability, and how they profit from their unique position in financial markets.

Table of Contents

Introduction to Market Making

Financial markets exist to facilitate the exchange of stocks, bonds, currencies, commodities, and derivatives. For these trades to happen smoothly, there must be a sufficient number of buyers and sellers at any given time. When an investor wants to sell an asset, they need a buyer ready to purchase at an agreeable price—and vice versa. However, markets can sometimes face periods where buyers and sellers do not actively place orders, leading to illiquidity and sudden price jumps (or drops).

Enter the market maker: an individual, a group of individuals, or a specialized firm registered with an exchange to buy and sell securities on a continuous basis. This function directly supports the smooth operation of the market by ensuring there is always an active bid and ask quote, even when general market participation is low.

Market makers are the proverbial “oil” in the trading machine. Without them, markets could experience significant delays, wide bid-ask spreads, and more frequent price dislocations. In this article, we delve deep into how market makers operate, the risks they take, the strategies they employ, and how they earn a profit by handling inventory and facilitating trades.

The Importance of Liquidity in Financial Markets

Before diving into the specifics of market making, it’s crucial to understand why liquidity is so pivotal:

- Efficient Price Discovery

Liquidity allows prices to be determined through numerous buyer-seller interactions. When many participants place orders, the resulting transaction prices reflect the broader market consensus. - Tighter Bid-Ask Spreads

Liquidity typically narrows the bid-ask spread, making the cost of trading cheaper for all participants. - Reduced Price Volatility

High liquidity helps absorb large buy or sell orders without causing disproportionate swings in the asset’s price. - Investor Confidence

A liquid market reassures investors that they can easily enter or exit positions at or near the prevailing market prices.

Without liquidity, even high-quality assets could become “stuck” because there aren’t enough counterparties willing to trade. This underscores the vital role of market makers in continually supplying liquidity to financial markets.

What Is a Market Maker?

A market maker is an exchange-registered participant obligated to maintain bid (buy) and ask (sell) quotes throughout the trading day. Market makers perform several key functions:

- Provide Constant Quotes: They regularly update prices at which they’re willing to buy (bid) and sell (ask).

- Facilitate Trades: By stepping in to buy from sellers and sell to buyers, they ensure continuous market operation.

- Absorb Imbalance: If there are more sellers than buyers at a given time, a market maker might buy assets to prevent prices from crashing, and vice versa.

Market makers focus on specific securities—like certain stocks or currency pairs—and are often tasked with maintaining minimum spread requirements and quote sizes. They usually enjoy lower commission rates or other incentives from exchanges for helping maintain orderly markets.

Why Do Market Makers Exist?

- Profit Motive: First and foremost, market makers aim to profit from the spread—the difference between the price at which they buy (bid) and sell (ask).

- Exchange Incentives: Many stock exchanges provide rebates, reduced fees, or other perks to firms that register as market makers. This helps encourage more consistent trading flows.

- Regulatory and Functional Necessity: Exchanges and regulatory bodies often require designated market makers or specialists to ensure that markets function efficiently, especially for less-liquid stocks.

- Market Stability: Market makers help stabilize prices by absorbing temporary imbalances in supply and demand. Their activity limits excessive volatility and sudden price spikes or drops.

Without market makers, many assets—especially those not heavily traded—could experience wide price fluctuations, making it difficult and costly for investors to execute trades at fair prices.

Core Mechanics of Market Making

Quoting Bid and Ask Prices

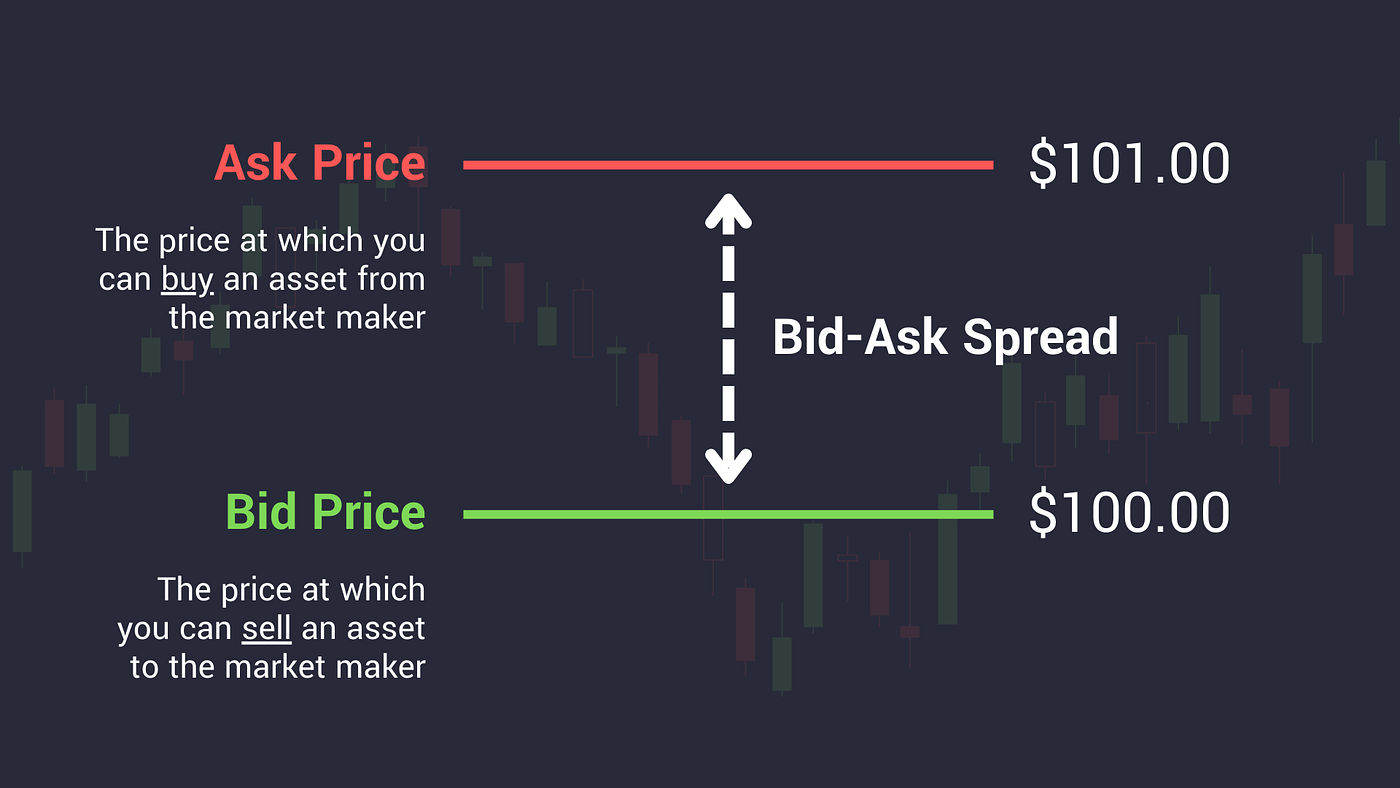

Bid and ask prices form the heart of market making. The bid price is the amount the market maker is willing to pay to buy an asset, while the ask price is the amount at which they’re willing to sell. These quotes are constantly updated to reflect:

- Real-time market conditions

- Inventory levels

- Overall demand and supply

- Historical and expected volatility

Market makers typically use sophisticated algorithms to adjust their quotes dynamically, aiming to remain competitive while mitigating unnecessary risk.

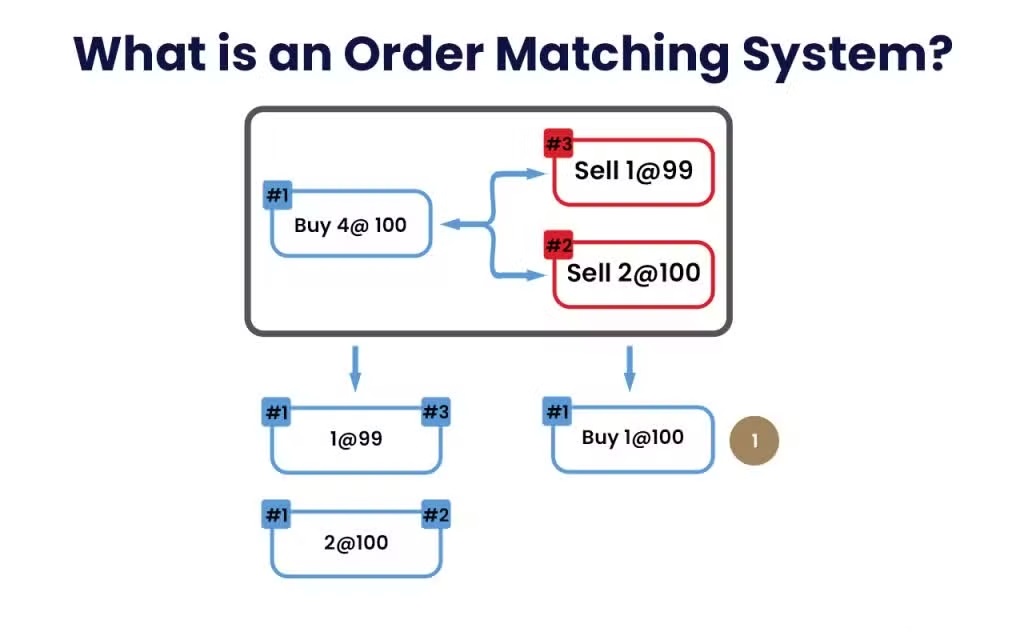

Order Matching and Market Fluidity

When a trader places an order—say, a market order to sell—if no other trader is immediately available to buy, the market maker stands ready to purchase those shares at the quoted bid price. Conversely, if a trader places a market order to buy, the market maker provides shares at the quoted ask price. This immediate execution fosters fluid market conditions, ensuring minimal delays for traders who want to transact quickly.

Inventory Management

Managing inventory is critical for a market maker. They don’t want to accumulate too large a position in any single asset, as this can become a significant risk if prices move against them. To manage inventory:

- Diversification: Holding multiple securities can mitigate the risk that any one asset’s price collapses.

- Hedging: Using derivatives or offsetting positions to limit exposure to price changes in the underlying asset.

- Dynamic Adjustment: Market makers constantly alter bid-ask quotes and order sizes to control their net inventory levels.

Risk Management

Market makers face a variety of risks, including:

- Price Volatility Risk: Sudden market moves can rapidly alter the value of their inventory.

- Liquidity Risk: In certain market conditions, it might become hard to offload large positions without pushing prices in an unfavorable direction.

- Operational Risk: Errors in algorithmic trading, technology outages, or mispricing can lead to substantial losses.

Sophisticated monitoring systems track positions in real-time, updating quotes the moment risk thresholds are approached. This combination of technology and strategy helps market makers balance their core objective—providing liquidity—with the need to protect their capital.

The Bid-Ask Spread: The Market Maker’s Profit Center

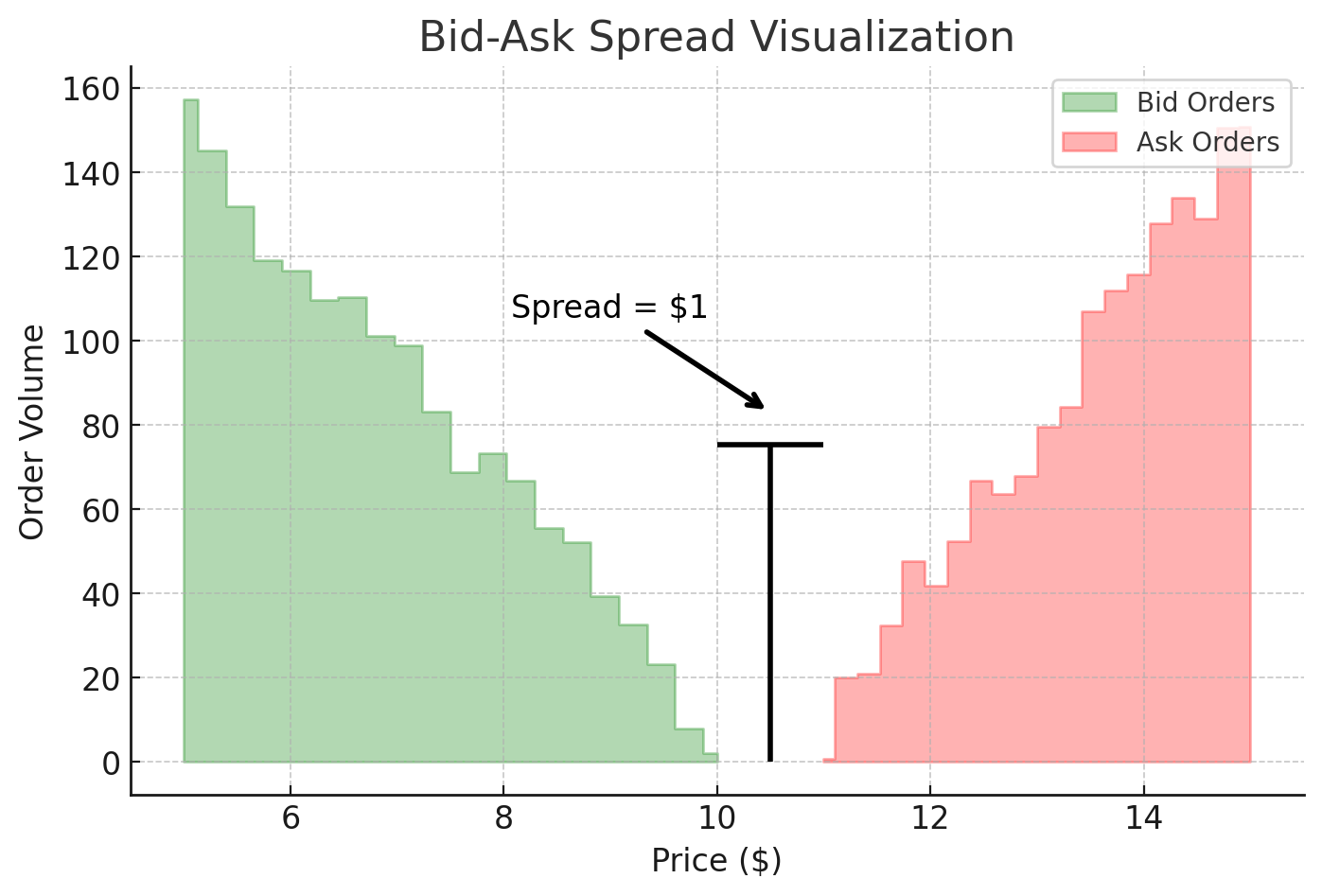

The bid-ask spread is essentially the difference between the market maker’s buy price (bid) and sell price (ask). For example:

- Bid: $10

- Ask: $11

- Spread: $1

If the market maker buys shares at $10 and then sells them at $11, the profit per share is $1. Over many transactions, these profits can accumulate substantially, especially in highly liquid markets with large trading volumes.

However, in real-world markets, spreads are often much narrower—sometimes as tight as $0.01 for heavily traded, high-volume stocks. Still, even a one-cent spread on millions of shares traded each day can translate into significant earnings for a market maker.

Key point: While capturing the spread is the fundamental driver of market-making profits, market makers must handle the inherent risk. A change in market conditions can quickly erode or reverse any gains if the price moves against the market maker’s inventory.

Example of a Basic Order Book

To illustrate how market making works, consider a simplified order book:

| BUYERS | SELLERS |

|---|---|

| 1000 shares @ $10 | 5000 shares @ $11 |

| 2000 shares @ $9 | 10000 shares @ $12 |

| 2000 shares @ $8 | 1000 shares @ $15 |

| 1000 shares @ $7 | 1000 shares @ $6 |

- The highest bid (someone willing to buy) is $10 for 1000 shares.

- The lowest ask (someone willing to sell) is $11 for 5000 shares.

A market maker in this scenario might post quotes like:

- Bid: $10 (willing to buy 1000 shares)

- Ask: $11 (willing to sell 1000 shares)

If they buy 1000 shares at $10 and then immediately sell those shares at $11, the profit is $1 per share or $1000 total. This cycle repeats as long as the bid and ask remain at those levels and the market maker can find counterparties at those prices.

But what if the market moves?

If a large seller suddenly enters the market and pushes the ask price down to $8, the market maker who bought at $10 might have to sell at $8, incurring a $2 per share loss.

Passive vs Aggressive Market Participation

Passive Orders

A passive order is placed at a limit price that waits for the market to come to it. For instance:

- If the current bid is $10 and the ask is $11, placing a limit order to buy at $10 or below is a passive action. The order sits in the order book until a seller is willing to accept $10.

Market makers often use passive orders to “add liquidity” to the market. By placing limit buy orders (bids) and limit sell orders (asks), they wait for participants to trade at these set prices.

Aggressive Orders

An aggressive order executes immediately against existing orders in the order book. Examples include:

- Market orders: You buy or sell “at the market,” meaning you accept the best available price right away.

- Limit orders at or above the current ask price: If the best ask is $25.30, placing a buy limit order at $25.30 (or higher) means you’re aggressively taking liquidity.

When a trader places an aggressive order, they “take liquidity” from the market. In contrast, the party with a resting limit order (the passive participant) is “adding liquidity.”

Providing Liquidity: How Market Makers Add Depth

Market depth refers to the number of buy and sell orders at different price levels. A deep market has multiple orders stacked on each side of the current price, making it easier to execute large trades without dramatically moving the price.

Market makers significantly enhance market depth by posting bids and offers across various price levels. For example, if you want to buy 20,000 shares at $10, and the order book already shows 1,000 shares available at $10, placing your 20,000-share order at the same price means there are now 21,000 shares on the bid at $10. A large seller wanting to sell 5,000 shares can do so entirely at $10 instead of driving the price down.

By continually placing and updating their orders, market makers ensure that:

- The market can handle larger orders with minimal price disruption.

- Sudden shifts in supply and demand are partially absorbed, preventing extreme price volatility.

Market Makers and Price Stabilization

Price stability is one of the most critical roles played by market makers. In a typical scenario:

- Excess Buying Pressure: If many traders want to buy a stock at once, the price might surge quickly due to limited sellers. A market maker steps in to sell from their inventory, providing a buffer that slows or mitigates rapid upward price spikes.

- Excess Selling Pressure: Conversely, if numerous participants want to sell simultaneously, the price could collapse. A market maker buys some of those shares at the bid price, helping stabilize the price.

This constant push and pull around the market price prevents extreme fluctuations—especially in stable, highly liquid markets—and aids the overall confidence and predictability of the trading environment.

Risks Involved in Market Making

Inventory Risk

Inventory risk is the possibility that a market maker’s holdings will lose value before they can be sold at a profit. Because market makers continuously buy from sellers and sell to buyers, they can end up with large positions that might become vulnerable if market sentiment suddenly reverses.

Price Volatility

High volatility can be lucrative for market makers if they manage it properly—spreads can widen, and trading volume can surge. However, extreme volatility can quickly turn profitable positions into losses, particularly if the market maker can’t adjust quotes or hedge fast enough.

Regulatory and Compliance Risks

Market makers must adhere to numerous regulations. Failure to comply can lead to penalties or the loss of market-making privileges. Regulations vary by jurisdiction but can include:

- Minimum capital requirements.

- Obligations to maintain two-sided quotes within a certain percentage of the last trading price.

- Reporting and record-keeping responsibilities.

Technology and Modern Market Making

High-Frequency Trading (HFT)

High-frequency trading involves using powerful computers and algorithms to execute trades in milliseconds or even microseconds. Many modern market-making strategies fall under HFT because speed is crucial:

- Latency Arbitrage: Exploiting price discrepancies across different trading venues in near real-time.

- Automated Quote Adjustments: Updating bids and asks dynamically to stay competitive while limiting risk.

Because HFT firms can process massive data streams so quickly, they often outcompete traditional human-driven market makers for speed, effectively replacing manual market-making to a large extent.

Algorithmic Trading Systems

Algorithmic trading uses automated strategies to determine when and where to place trades. This can include:

- Statistical Models that predict short-term price movements based on historical patterns.

- Market Sentiment Analysis through news or social media to anticipate supply/demand shifts.

- Machine Learning approaches that adapt to changing market conditions over time.

Algorithmic trading systems allow market makers to constantly monitor thousands of data points, adjusting their inventory and quotes to minimize risk and maximize profitability.

The Role of Regulation in Market Making

Regulators enforce rules that maintain fair and orderly markets. Key objectives include:

- Preventing Manipulative Practices: Market makers must not engage in tactics like spoofing or layering, which can mislead other participants.

- Ensuring Adequate Capitalization: Regulators want to ensure that market makers have enough capital to honor their obligations, even during market stress.

- Promoting Transparency: Requiring real-time reporting of quotes and trades helps all participants see current market conditions.

Depending on the exchange and jurisdiction, market makers might be designated as “specialists” or “designated market makers (DMMs)” with specific obligations. Breaching these obligations can result in penalties or revocation of market-making privileges.

Market Making Strategies

While the core idea is straightforward—buy low, sell high—various specialized strategies can be employed to enhance profitability or hedge risks.

Statistical Arbitrage

Statistical arbitrage (stat arb) involves using quantitative models to identify short-term price anomalies or correlations between related assets. A market maker might, for example:

- Go long on one stock while shorting a correlated stock if the data suggests they will converge in price.

- Use historical volatility and correlations to hedge the inventory in real-time, locking in spread-based profits with minimal directional exposure.

Event-Based Market Making

In event-based trading, a market maker may adjust quotes aggressively around major announcements—like earnings releases, economic data, or geopolitical news—that can trigger large price moves.

- Pre-Event Positioning: Widening spreads to account for higher uncertainty.

- Post-Event Reaction: Quickly updating quotes based on market reactions to the news, aiming to profit from the sudden surge in trading volume.

Pairs Trading

Pairs trading involves trading two related securities to capture differences in their price movements. For market makers focusing on multiple but correlated stocks or ETFs:

- When the spread between two correlated securities widens beyond a historical norm, the market maker buys the underpriced security and sells the overpriced one.

- When the prices converge, the position is unwound for a profit.

This strategy allows market makers to maintain a market-neutral stance while still leveraging their role as liquidity providers.

Challenges Facing Today’s Market Makers

- Increasing Competition: Automated trading firms use cutting-edge technology to quote tighter spreads, leaving thinner margins for traditional market makers.

- Regulatory Complexity: Regulatory obligations can increase operational costs and limit the flexibility of market makers, especially across multiple international markets.

- Technology Upgrades: Maintaining ultra-low latency infrastructure is expensive but often necessary for staying competitive.

- Liquidity Fragmentation: The rise of multiple exchanges and alternative trading systems (ATSs) has scattered liquidity, forcing market makers to operate in numerous venues simultaneously.

- Sudden Volatility Events: Flash crashes or black swan events can lead to large, rapid losses if a market maker fails to adjust quotes fast enough.

The Future of Market Making

Market making will likely continue to evolve as technology, regulations, and market structure change. Some key trends include:

- Greater Automation: Algorithmic strategies and AI-driven models will handle an even larger proportion of market-making tasks.

- Cryptocurrency Markets: As digital asset markets grow, specialized crypto market makers are emerging, providing liquidity in exchanges that operate 24/7.

- Consolidation: Smaller market-making firms may merge or be acquired by larger players that can invest heavily in cutting-edge infrastructure and meet capital requirements more easily.

- RegTech Solutions: Technology designed to help firms comply with complex regulations will become increasingly important, ensuring real-time monitoring of market maker obligations.

Conclusion

Market makers are essential for keeping financial markets liquid, stable, and efficient. By continuously placing bid and ask quotes, they facilitate instant order execution, help stabilize prices during periods of supply-demand imbalance, and narrow the bid-ask spread—all while managing significant risks tied to inventory and price volatility.

- Liquidity: Their constant presence in the market ensures that traders can enter and exit positions without drastic price changes.

- Stability: By absorbing surges in buying or selling pressure, they maintain more orderly price movements.

- Profitability: Through careful inventory management and risk controls, market makers earn profits from the spread, ideally balancing frequent small gains against occasional losses.

As markets become more technology-driven, traditional human market making has largely given way to algorithmic and high-frequency approaches, but the core principles remain the same. Market makers stand at the intersection of buying and selling interests, ensuring that trades can happen smoothly. This role benefits everyone from individual retail traders to large institutional investors, reinforcing the critical importance of market makers in today’s global financial ecosystem.

Final Takeaways

- Market making is fundamentally about ensuring liquidity—the ability to buy or sell quickly without severe price movement.

- Market makers provide continuous two-sided quotes (bid and ask) and profit from the spread.

- Risk management is crucial; inventory risk and rapid price movements can turn profitable positions into losses.

- Technology has revolutionized market making, with algorithmic trading and HFT dominating the modern landscape.

- Regulations aim to keep the playing field fair and transparent, requiring market makers to maintain certain standards and preventing market manipulation.

- While challenges like intense competition and technology costs persist, market makers remain an indispensable part of financial markets—ensuring stability, confidence, and efficiency.

By understanding how market makers operate and the crucial role they play, investors gain deeper insight into the mechanics that drive everyday trading. Whether you’re a retail trader, an institutional investor, or simply a market enthusiast, recognizing the function and strategies of market makers can help you navigate and appreciate the complexities of the financial world with greater clarity.